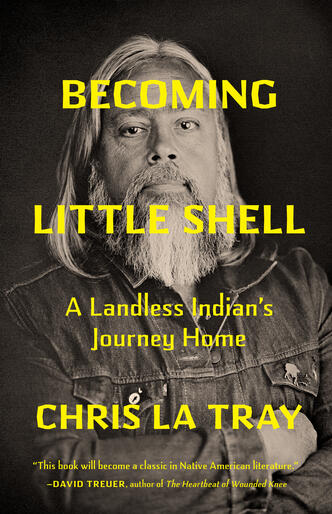

A Q&A with Chris La Tray, author of debut Memoir Becoming Little Shell

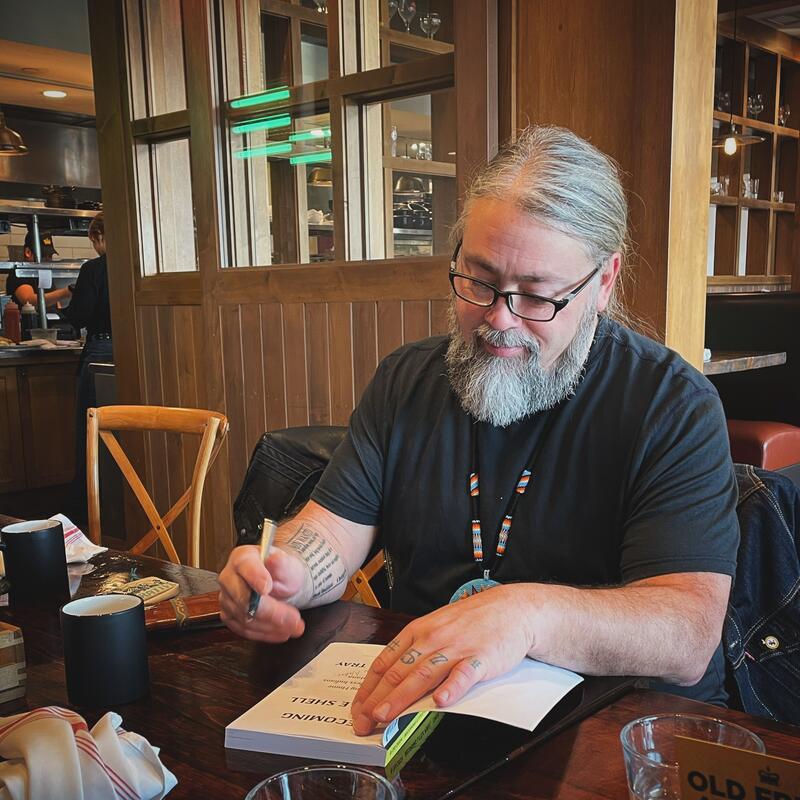

At Milkweed, we often discover great books in curious ways, and the Métis poet and storyteller Chris La Tray’s debut memoir, Becoming Little Shell: A Landless Indian’s Journey Home, is no exception. Nearly a decade ago, Publisher & CEO Daniel Slager attended a writers conference in Missoula, Montana. There he crossed paths with La Tray, who was hand-selling books at local indie bookstore Fact & Fiction. Their exchange morphed from pleasantries to serendipitous dialogue revealing that La Tray was writing a book of his own.

Later that evening, Slager learned that La Tray had recently begun interrogating his origins, captivated by the alluring-yet-elusive suggestion of Chippewa heritage in his bloodline. For though his grandmother had admitted to as much, La Tray’s father vehemently contested their Indigenous identity until his death in 2014. But La Tray’s curiosity persisted. Over a decade prior, he recalled attending his grandfather’s funeral and observing countless Natives in attendance.

“Here was a collection of people I’d never known but was clearly connected to,” he reflected. “Who were they? Why didn’t I know them? Why was I never allowed to know them? What is the story of our family?”

These questions would fuel the turning point in La Tray’s adult life—and become the catalyst for his investigative debut memoir, which retraces familial, geographical, and tribal histories.

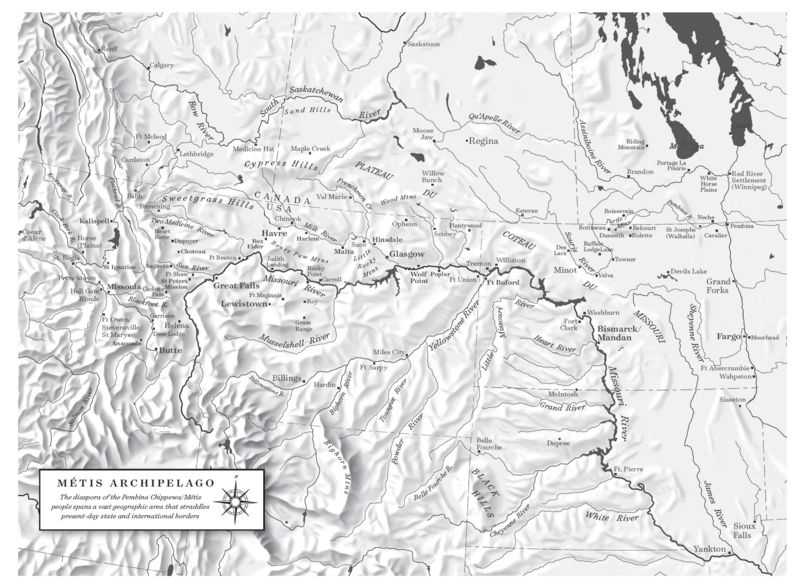

Over the next seven years, Slager and La Tray collaborated on four rounds of developmental edits to the manuscript. The result is a piercingly beautiful narrative of a person, a place, and a people that maps mutually uncharted journeys of belonging. As the dual storylines of La Tray’s search for his true identity (and later, tribal enrollment) and the Little Shell Chippewa Tribe’s fight for federal recognition become inextricably intertwined, La Tray unearths over one hundred and fifty years of obfuscated history. In passionate-yet-approachable prose, he renders a compelling argument for why the past must not be ignored, illuminating his own experience as an example of the kinds of devastating consequences ignorance promises to enact into the future.

We are thrilled to publish Becoming Little Shell in the Fall of 2024. Read on for a first look at the impetus behind the work, as La Tray opens up to our staff in the following interview.

*

Milkweed Staff (MS): Becoming Little Shell follows your journey to discovering you are part of the Little Shell tribe and the process of becoming a member; at what point did you know you wanted to write about this experience?

Chris La Tray (CLT): It was rattling around in my mind for a while, but I didn’t really realize it until I met the Métis folklorist Nicholas Vrooman in 2013 and told him I was thinking of writing about it. That was the first time I’d actually said it aloud but also not that surprising; I think most writers are constantly adding to a rolodex of book ideas until suddenly one demands attention.

MS: Your memoir covers Indigenous history and also brings readers all the way up to the present tense. Why did it feel important to include this more general history alongside your own personal history?

CLT: As a people whose history has largely been erased by colonial historians, there isn’t a lot about us out there, or it’s scattered. I wanted to write something for people like me who are searching for knowledge about where we came from and searching for a solid overview. That’s the thing I hope most to have achieved with this book.

MS: At various points in Becoming Little Shell you share experiences of your father and grandparents, even though your father, for instance, denied the truth of your shared heritage. How did you navigate sharing these stories despite knowing that some of the people involved would feel conflicted about their experiences being made public?

CLT: It helps that they have all moved on to the other side—but their stories aren’t unique. As I learned pretty early on, that [fraught, disconnected] relationship to their heritage is pretty common to Native people of their generations. My mom says she thinks my dad would be proud if he read my work today. I don’t know. I think my grandmother would be over the moon.

MS: There are so many gorgeous passages about the landscape of Montana throughout various times in your life. Can you say more about how your relationship with the natural world informed this book?

CLT: There is no life to write about without relationship and reciprocity with the natural world. It isn’t any more separate from my survival than my lungs or my heart. The land is the first storyteller of this world, and whenever I struggle to find answers, I look to the land for solutions.

MS: You also delve into the concept of “blood quantum” laws in your book, and their lasting effects on induction processes for tribes. What do you hope readers will take away from reading about this especially polarizing topic?

CLT: Genocide isn’t just a body count resulting from guns and bombs and the like, though inflicting that violence on people has been a key part to the United States’ strategy all along. Genocide can also take the form of elimination by attrition, and that is what blood quantum does. It’s a long game toward the eradication of entire cultures.

MS: Becoming Little Shell includes references to scholars and authors who have also written about the history of the Little Shell tribe. Can you recommend further reading for readers who might be interested in learning more?

CLT: The book has a full bibliography of where I learned what I know, even books that didn’t inform the text so much as just expanded my thinking. This is an ongoing story that I will probably be writing about for the rest of my life, and the reading list is constantly expanding. That said, people need to learn about where they live. Indigenous people were there wherever a reader finds themselves, and they need to learn that story. Most tribes have tales of violence against them, trails of tears from removal, and more. I hope readers everywhere will feel encouraged to learn and reflect on these stories more deeply.

MS: You are the current poet laureate of Montana and have also worked for many years as a bookseller there. How did your involvement in Montana’s literary community play a role in the creation of this book?

CLT: This book wouldn’t exist without my involvement in this great community in Montana—particularly my relationship with Fact & Fiction Books. If Mara Panich, the incoming manager then and now-owner (taking over for the store’s legendary and about-to-retire Barbara Theroux in 2016) hadn’t, during a period when my grub stake was running out, asked me the fateful question: “You want a part-time job with shitty hours and horrible pay?” and I hadn’t answered with an exuberant, “Yes!” then who knows what I would be doing right now. Everything good that has happened to me as a writer blooms from that beginning. My love and gratitude for everyone who has helped me along the way is unmeasurable.

MS: What do you hope will most resonate with readers after encountering your memoir?

CLT: That the Little Shell Tribe of Chippewa Indians are here, have always been here, and that we are mighty.