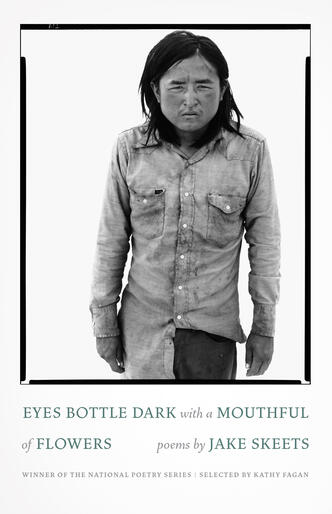

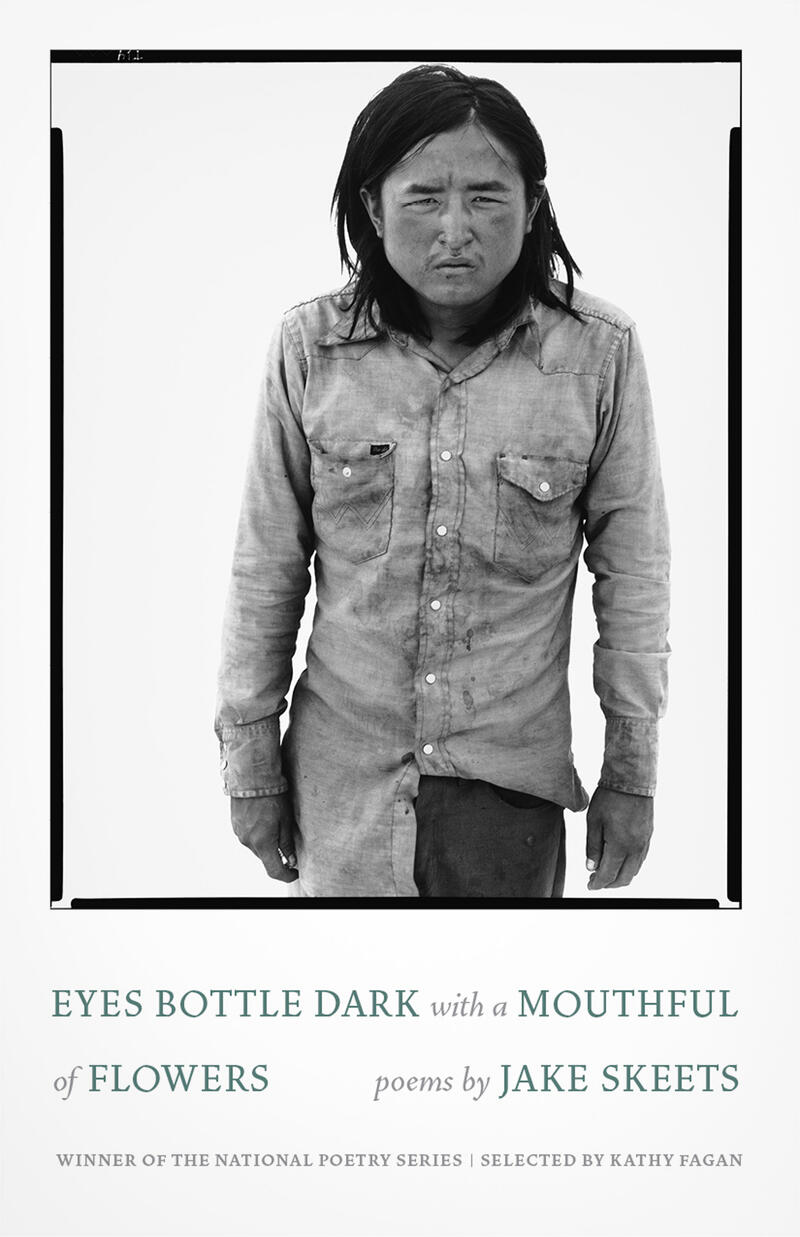

Drifting: A Cover Image Story

by Jake Skeets

In the summer of 1979, Richard Avedon was in the middle of a project taking portraits of people in the American West under the sponsorship of the Amon Carter Museum in Fort Worth, Texas. In 1979, Richard Avedon came across my uncle, Mr. Benson James in the streets of Gallup, New Mexico and decided to take his portrait. Of course, the details of the exchange are unknown as a year later Benson was stabbed more than 20 times in Gallup. In 1985, Richard Avedon sent a signed copy of In the American West to Benson and it was received by my mother, her sisters, and my grandmother. Shocked, they sent a letter back to Richard Avedon stating that Benson had passed away five years before. I came across the letter while researching the portrait and the circumstances surrounding it.

I distinctly remember seeing the image for the first time. As a child, I did not understand the importance of the portrait. I returned home as an adult years later to this image. I asked my mother to show me the portrait again and I saw the image for the first time again. I saw the title: “Drifter.” I saw the dollar bills folded in my uncle’s hand. I saw the stark bleached background and the way his skin contrasted the whiteness. I saw his eyes, bottle dark. The color of his eyes are the color of my eyes, the color of lovers’ eyes, the color of my brothers and cousins’ eyes: bottle dark. For the first time, I saw myself as him. I saw my brothers and cousins, too.

In the Foreword of In the American West, Avedon stated he used an 8x10” view camera and did not stand behind it to photograph his subjects. His crew would tape large white sheets of paper to a building side or some other vertical surface. He asked his subjects to stand still as required by the camera. He stood only a few feet from them and took the pictures. He worked in shade as light would give shadows and Avedon wanted the source of light to be invisible. He wanted background to be invisible. The only positionality my uncle has is the fact that his portrait is a few pages into the book. This man, a photographer of people like Ronald Reagan and Marilyn Monroe, took my uncle’s portrait in 1979 and in 1980 my uncle was gone. This brings a whole new layer to the popular belief that Native people refused to be photographed out of the fear that their spirit would be taken.

It seems Navajo men are often drifters, drifting through the whiteness taped up by white men. They walk about with invisible light and no shadows so no one can tell the difference between 1979 and 2019, between a morning sky and an evening one. Richard Avedon colonized the page and stole everything from it. My project became the returning of something back to the page and to the portrait of my uncle. To show that, though men drift through this world, they do so speaking with words that are inherently sacred. They speak with mouthfuls of flowers, of beauty. Of course, some men are dark and cause damage. They use words to steal.

Richard Avedon further notes in the Foreword, “There is no such thing as inaccuracy in a photograph. All photographs are accurate. None of them is the truth.” He continues, “The first part of the sitting is a learning process for the subject and for me. I have to decide upon the correct placement of the camera, its precise distance from the subject, the distribution of space around the figure, and the height of the lens. At the same time, I am observing how he moves, reacts, expressions that cross his face so that, in making this portrait, I can heighten through instruction what he does naturally, how he is.” It seems as though poetry and photography share an awful lot. Richard Avedon approached the page much like a poet, much like me. That would then make my uncle a poem. The fact that Avedon could strip the page of everything frightens me and guides me whenever I approach the page to start a poem. The ability we all have to create and destroy worlds.

As I look at the portrait now, it seems that my uncle is still trying to replace what was made invisible in his portrait, what was stolen from it, with only his body. He is holding onto the remnants of story, beauty, and chaos in a space made to appear empty.

My book is trying to do the same thing and it is only fitting that this image preface the book. Everything was too coincidental to be a coincidence. The fact that my book would be published in September 2019 on the 30th anniversary of the taking of this portrait. The fact that my book focused on the many dark stories families have about Gallup, New Mexico. It seems fitting to return my uncle’s portrait to story, beauty, and chaos. It seems fitting to try to do something. I do not want to exploit my uncle’s portrait. I also do not want to attack Richard Avedon. That is not the project with this book cover choice.

There is a Navajo creation story about the creation of night and day. To summarize briefly as this may not be the appropriate time to tell the story, animals played a shoe game. Day and night animals composed teams for the game to decide if there would eternal day or night. The game went on for hours and settled as a tie so daylight and nighttime would be equally shared. The point of this digression is to offer the importance of balance. A thing cannot exist without balance much like a poem cannot exist without balance. Balance between the text and white space, between craft and desire, between metaphor and simile. So the project of this book and this book cover choice is to find something like that balance. I want to add what was made invisible. I want bring the light back so we can have our shadows again. To give us back the morning so we can have the night.

Eyes Bottle Dark with a Mouthful of Flowers is now available for pre-order! And, as a special bonus: the first 100 pre-orders will receive a free, limited-edition signed broadside of the poem “Dear Brother.” Broadsides will be shipped with book orders in late August for delivery on or before publication date.

Pre-order now»